Construction Materials Prices in Syria

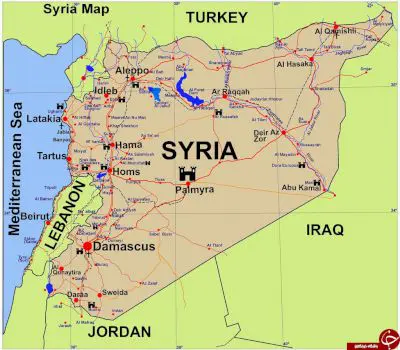

Syria is located in West Asia, north of the Arabian Peninsula in the Middle East. Building materials are used in the construction and production of various structures. The Syrian government grants temporary imports of goods to other countries without paying taxes in the following cases. Fine sand is usually easily found on the beach and in the river. Syria is a pristine export market for Iranian products due to the situation in Syria due to sanctions. Plaster is a soft, white powder obtained from gypsum

Add your import and export orders to this list

Warning: Undefined variable $formTitle in /home/anbar/domains/anbar.asia/anbar/inc/html/desktop/orderform.php on line 10

Warning: Undefined variable $marketName in /home/anbar/domains/anbar.asia/anbar/inc/html/desktop/orderform.php on line 12

Warning: Undefined variable $location in /home/anbar/domains/anbar.asia/anbar/inc/html/desktop/orderform.php on line 12

If you want to trade in the , please join in Anbar Asia. Your order will be shown here, so the traders of contact you

Syria earns millions of dollars annually through its ports on the Mediterranean Sea. The construction industry is one of the most prosperous industries and businesses in the Middle East. The banking system in Syria is under the control of the Syrian government, and all Syrian banks operate under the Ministry of Economy and Trade. Soil is a combination of excellent minerals and minerals created by weathering and rock destruction

- Syria Sand Market

- Syria Cement Market

- Syria Clay Market

- Syria Concrete blocks Market

- Syria lime Market

- Syria Brick Market

- Syria paint Market

- Syria wood and timber Market

- Syria Glass Market

- Syria Ceramic Tile Market

- Syria Plaster Market

Gravel smaller than sand is called fine sand. Fine sand is usually easily found on the beach and in the river. In civil engineering, according to the classification, ASTM called fine sand for gravels smaller than 4.75 mm and coarser than 0.075 mm of.

Read More ...

Clay is one of the types of sticky soils that is used in construction. This soil is the result of erosion of metamorphic and igneous rocks and because of its very fine grains, it is also called colloid. The important point in using this material is to choose a quality sample of it. Clay is the best material that can be used to control the temperature of the building.

Read More ...

Whitewash plaster: The price of whitewash plaster is very reasonable. This plaster is used to cover the surface and whitewash the walls, and its color is completely white.

Read More ...

The combination of cement with water creates a hard material called concrete, which plays an important role in strengthening various structures.

Read More ...

The Syrian economy is known as a state economy. The lack of strong financial resources and infrastructure in the private sector, as well as government interference in the economy, has put the country in a difficult economic situation.

Read More ...

Sand is produced by crushing rocks. Coarse stones are produced from the crushing and separation of natural stones, and finer sands, in addition to stones, also contain shells and corals. In civil engineering, aggregates smaller than 75 mm and coarser than 4.75 are called sand. Sands are divided into two categories according to the source and type of grains used in construction.

Read More ...

Clay soil is a term that refers to sedimentary rocks containing a significant amount of clay minerals, such as rock. Iran is one of the special regions of the world that has many resources; The export capacity of clay from the waters of Chabahar port to Pakistan shows that Iran has the richest resources.

Read More ...DEIR EZ-ZOR, Syria (North Press) – In light of Iranian-backed factions’ monopolization of imports and trade of construction materials, 32-year-old Youssef al-Awwad, a resident from the city of Abu Kamal in Syria’s regime-held Deir ez-Zor, was forced to sell his destroyed shop after being unable to reconstruct it due to the high expenses of construction materials. The 700,000 Syrian pounds (SYP over $200), which he saved during the past two years no longer has value in light of the increasing prices of construction and cladding, according to al-Awwad. Prices of construction materials have increased as officials of Iranian-backed pro-Syrian government factions monopolize trade in Deir ez-Zor, especially the trade of construction materials, according to residents. As a result of the decreasing value of the Syrian pound and US sanctions imposed on the government and its officials, most residents of the areas are witnessing increasingly deteriorating living conditions. Iranian-backed Harakat Hezbollah al-Nujaba and Liwa Fatemiyoun are the most prominent groups that monopolize the trade of construction materials in the areas in Deir ez-Zor and its villages. “Recently, the two Iranian-backed factions have assigned traders close to them as economic mediators in order to deal with traders in the market and monopolize the trade of construction materials, as well as to avoid the imposed economic sanctions,” Isam al-Jasem (a pseudonym), a trader of construction materials in Abu Kamal city, told North Press. Meanwhile, the Deir ez-Zor countryside mainly relies on Iraqi construction materials transferred through the economic mediators of those factions to Syria “to facilitate their movement through the checkpoints, routes, and crossings in both Syrian and Iraqi territory,” according to traders. Two days ago, the US administration announced the inclusion of Iraq’s Kata’ib Hezbollah, Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq, and both Russia- and Syria-based companies on the sanctions list. “Even trucks that transfer construction materials are directly owned by Iranian-backed factions and they are run by the economic mediators in order to avoid being sanctioned or monitored,” Jabar al-Ali (a pseudonym), an official in the Syrian National Defense Forces (NDF) militia told North Press. “The trucks enter through military routes through the illegal crossing of al-Sekak with Iraq in the vicinity of Abu Kamal, where the Popular Mobilization Forces dominates from the Iraqi side and Iranian-backed Liwa Fatemiyoun from the Syrian side,” he added.

Read More ...

Prices of building materials in Syria A ton of iron arrives to a million and a half Syrian pounds, and a ton of cement is 120,000. The price of a ton of brominated iron jumped to its highest price in Syria for more than 10 years, when the price touched the levels of one million five hundred thousand pounds, while the price of a ton of cement ranged between 100 and 120 thousand SP on the black market affected by a price increase in government institutions that raised Its price ranges from 46 thousand to 70 thousand. © 2019 Re-Build Syria All rights reserved to Al-bashek for trading and exhibitions , Designed by Web Gates. Cement tiles are an instance of the new materials of construction that characterized the architecture of Modernity in Syria and Lebanon beginning in the late nineteenth century. It was an effect of major upheavals that struck Syrian society in the wake of the Egyptian expedition (1831-1840). Therefore, this survey’s analyses and conclusions seek to articulate the impact of the esthetic, industrial, and commercial of the cement tiles, as well as the historic dimension of their employment, the Syrians’ tendency toward imitation and renewal, the acceleration of contacts with Europe, and in the ways of production and consumption. Although cement tiles were for decades the most widely utilized floor covering material in Syria and Lebanon, its importation and local manufacturing have not been the thrust of specialized Thus, the aim of our survey is to build on previous work and to propose an established historiography of the importation and the local manufacturing of cement tiles in a defined temporal and geographical framework: Damascus and Beirut, from the 1880s to the 1930s. This article is a result of previous investigations undertaken in the context of post-doctoral research in the Department of Art History and Musicology at the University of Geneva, focusing on the development of materials and techniques of construction in Syria and Lebanon from the late nineteenth century to the mid-twentieth century. 1 Cement tiles (al-balāṭ, al-balāṭ aṣ-ṣinā’i, al-balāṭ al-mosaīk, al-balāt al-moulawwan al-‘aḥjār al-ramliyyah or al-‘aḥjār shaped an occurrence of the new construction materials that have characterized the architecture of modernity (al-fan al-‘aṣri)2 in Syria and Lebanon since the late nineteenth century. It was an effect of the major economic and sociopolitical upheavals that struck Syrian society beginning with the Egyptian Expedition (1832-1840). For that reason, the historic dimension of the use of cement tiles, the acceleration of contact with Europe, the evolving ways of production and consumption, and the Syrians’ penchant for imitation and renewal (ḥubbu at-taqlīdi wal tajaddod)3 should be considered. Accordingly, the present survey attempts to respond to the following crucial questions: What contextual elements enhanced the introduction and use of cement tiles? Who were the first local manufacturers? Who were the principal suppliers of machinery for the workshops? What role might be attributed to the importation and widespread diffusion of this material? What specificities characterized its manufacturing and use? Although cement tiles were for decades the most widely used flooring material in Syria and Lebanon, their importation and local manufacturing have not been the object of specialized inquiries. 6 The aim of the present survey is to build on previous work and to propose a historiography of the first importation of cement tiles and their local manufacturing within a defined temporal and geographical framework: Damascus and Beirut, from the 1880s to the 1940s. The previously mentioned topics will be clarified first through a general overview shedding light on the related political and economic context; followed by a focus illustrating the establishment of the first local workshops in Damascus and Beirut; and, finally, by a detailed investigation and analysis into the beginnings, development, and decline of cement tile importation. 3 These approaches will be based on resources consisting of three main parts: firstly, writings of authors who lived during the period in question; secondly, holdings in public archives in France, the United Kingdom, and Syria; and, thirdly, holdings in private archives related to companies involved in cement tile manufacturing and trade. Muhammad Awwād in the region of Damascus, and others. 4 The emerging modernist sociopolitical debate, as well as the promising economic situation characterizing the Syrian context from the mid-nineteenth century, shaped the acceptance, importation, and local manufacturing of mosaic and agglomerated cement tiles. In fact, Syrian architectural modernity should be seen as an aspect of a new pattern of civilization that restructured the traditional rules and convictions of society for several internal and external reasons. In spite of the visible impact of these changes, Syrians still sought to modernize their society according to three main approaches: the first, conservative, aimed at preserving existing sociocultural structures and rejected the concept of historical rupture; the second, liberal, strove to fundamentally transform society and actualize its natural development through the sciences and new ways of thinking; the third tendency hoped to adjust the irreversible movement of modern civilization to the local context, while accepting the supremacy of secularized societies exemplified by certain European models. 7 The reforms had different effects on the economic infrastructure of Syria and Lebanon, most notably on property, transport, and taxation regulations, and on restructuring industry, agriculture, trade, and construction activities. While economic interactions with Europe weakened several areas of the Syrian economy, especially the traditional artisanal industries, they also led to the modernization of urban and architectural space by bringing experts, investments in civil engineering projects, and related new techniques, machinery, and merchandise. The second, indirect, relates to the role of European capital in the development of the economic infrastructure of Syria and Lebanon from the mid-nineteenth century onwards. For instance, in the wake of the World War I, French investments in Syria and Lebanon totaled around 200 million francs. 12 The sectors that benefited most from this development were Syrian ports and railway projects. 8 On the other hand, the inauguration of the first passable road between Damascus and Beirut in 1863, followed by a railway in 1895, not only constituted political and technical advents but also served as the main catalyst for the two cities’ urban and architectural modernization. 16 As a result, Beirut emerged as “the leading port on the eastern and the “center of Syrian trade,”18 while Damascus opened a new page in the history of its relationships with the world. This situation remained more or less stable until March 13, 1950, when the customs union between Syria and Lebanon came to an end. 19 The constant increase in Beirut’s imports, from 99,761 tons in 1901 to 233,706 (two hundred thirty-three thousand seven hundred six) tons in 1910,20 proves the vitality of the Syrian economy during the late Ottoman period, when the United Kingdom, France, and Germany were the main European associates of the Ottoman province of Syria, or Šām Šerīf. 21 At any rate, it is not surprising that coastal cities such as Haifa, Beirut, and Alexandretta were the first to experiment with new machinery and construction materials. For instance, Damascus may have imported the first quantities of cement tiles or machinery for workshops through the port of Beirut. P reported on November 10, 1913 the growing commercial activities between the two cities offered the railway potential financial gains. He defined the transported quantities, indicating that Beirut and Haifa were in competition over the transit of Damascus importations. 22 The report illustrated the increasing quantities of construction materials transported from Beirut to Damascus: 1,490 tons in 1907, 2,558 tons in 1908, 4,799 tons in 1909, 7,264 tons in 1910, and 9,004 tons in 1911. The customs taxes of 11% levied on most imports, including construction materials such as cement, tiles, dyes, metallic beams and roofing tiles,24 continued to be applied until the end of the 1940s. 9 During the French Mandate in Syria and Lebanon, a new economic dynamic, more interlaced with Europe, took root. The porte ouverte customs policies imposed by the French led to disastrous consequences in several sectors, since Syria, a new economic entity, was not prepared for such international competition. 26 For that reason, traditional craftsmanship related to construction activities constantly fell behind, with the exception of modest initiatives linked to the Syrian Modern Style buildings. In light of this context, the following paragraph illustrates how the first cement tile workshops were established in Beirut and Damascus and explains who their first manufacturers, merchants, and importers were. 11 Machinery for workshops in Syria and Lebanon was purchased from Europe in two ways: from the 1880s to the 1900s by the manufacturers themselves, usually assisted by European trade mansions such as A. 31 based in Marseille; then, from the 1900s onwards, local trade companies imported the machinery from Europe for most Syrian and Lebanese manufacturers. 14 In addition to Chaya,39 the company of Derviche Haddad had a prominent role in the trade and manufacturing of construction materials, including cement tiles, since the 1890s. On the other hand, some documents from the 1930s also cite the sale of machinery and tools to Syrian workshops through Fouad el-Khoury. 46 Public and private archives illustrate Araman’s activities in the trade and manufacturing of construction materials, most notably cement, concrete pipes, cement bricks, ceramic and cement tiles. 7) to Khalil al-Bagdadi in Damascus and indicates potential deals with merchants from Lattakieh. 51 Accordingly, until the end of the 1940s Néjib Araman may have been the main agent of Lachave & Fils in Syria and Lebanon. Houssami & Co in Beirut in which it is clearly indicated that Araman & Fils was the exclusive agent of Lachave & Fils in Syria. from Beirut; Habib Antaki & Fils, Abdel Wahhāb Aṭṭār, and Letfallah Geabehan from Aleppo; and George Coeter from Damascus. 17 Damascus followed Beirut into the cement tile manufacturing. Although investigations conducted in view of preparing the Dictionary of Syrian aṣ-ṣinā’āt undertaken from 1892 to 1902,55 this valuable book does not mention any information about cement tile production. However, several documents have attributed the beginning of cement tile manufacturing in Damascus to the late 1890s. He mentions several “friends” who were manufacturing cement tiles in Damascus and includes a drawing related to the purchased press. Other documents prove that a certain Khalil al-Baghdadi had a prosperous cement tile workshop in Damascus active from at least 1909. 58 Additionally, correspondence related to merchants from Beirut and Aleppo give data about the cement tile manufacturers in Damascus. 7) to Khalil Bagdadi in Damascus and highlights potential deals with merchants from Lattakieh. 61 Other trading companies working in Damascus during the examined period, such as Obeid62 and Sehnaoui & Fils,63 might be mentioned as importers of cement tile machinery. In the wake of World War I, cement tiles were identified in buildings in Damascus thanks to the production of local workshops. According to Ṣalāḥ es-Ṣāleḥ, in 1933 Damascus was home to ten manufactures of cement tiles. 64 However, it seems that cement tile manufacturing in Aleppo was more prosperous than in Damascus. While the annual report of the French High sur la situation économique de la Syrie et du Liban, 1931—states the establishment of four modern cement tiles workshops in Aleppo between 1928 and 1931,65 it does not indicate any in Damascus. In 1927, Taqi ed-dine al-Ḥuṣni displayed his pride and admiration in finding a hydraulic press, working on oil, presented at the Fair of Damascus. In 1936, the newspaper al-Mashreq emphasized that local and imported machinery for tile and mosaic ṣun’i al-balāt exhibited at the Damascus Fair. al-Kurdi workshop in Damascus, 2014. In spite of this observation, the Annual Report, (Economic) (A) of the British Consulate in Beirut covering Syria and Lebanon for 1937 reveals that the cement industries in Syria and Lebanon were growing. 73 Muḥammad Kurd ‘Alī confirms this perception that World War II stimulated industrial output in Syria,74 including of cement tiles. 75 Finally, research in the field confirms that several cement tile factories active in Damascus during the period studied here are still operating today. 76 In 1970, the Marble and Cement Products Artisans Syndicate [MCPAS] was founded in Damascus. The mineral sources of these materials, including those for the production of Portland cement and hydraulic lime78 existed in most Syrian and Lebanese regions. 22 Building activities in Damascus relied on sand extracted from close land or mountain quarries. For instance, until the 1960s, the lands around al-Mazzeh village, four kilometers to the south of Old Damascus, were the main source of the sand utilized in building works as well as in cement tile manufacturing. Today, al-Mazzeh forms a district in Damascus. 80 However, most quantities used were extracted from local quarries, for instance, from Ruhaibeh, located 35 kilometers north of Damascus. For example, the catalogues of trade and navigation issued by the French Ministry of Commerce and Industry confirm the exportation of Portland cement to Syria in the 1890s. Gilly, director of the French Trade Office in Syria and Cilicia, stated that 15,000 tons of Portland cement, 960 tons of lime, and 12,000 tons of hydraulic lime were imported in the pre-World War I period. Furthermore, he requests the help of Lachave & Fils to appoint him as the exclusive dealer of the Pavin Lafarge Company in Syria, making use of the fact that Lafarge and Lachave & Fils were located in the same commune in France, Viviers. 25 Since the beginning of the French Mandate, Syria and Lebanon imported Portland cement through the ports of Beirut, Tripoli, Alexandretta, and Lattakieh. 92 In 1921, several French companies exported cement to Syria and Lebanon, including those companies that participated in the Beirut Fair: J. 93 The Economic Bulletins of the FHC mention several sources of Portland cement and rank them according to the volume exported to Syria and Lebanon. 26 Within this framework, two local factories opened in Syria and Lebanon: the first, the National Company for the Manufacturing of Cement and Construction Materials, was established in Dummar, near Damascus, in 1930. 100 Several factors encouraged the establishment of these manufactures and the realization of considerable outputs,101 especially increased construction activities and the abundance of the calcite in many areas in Syria and Lebanon. 28 Syrian builders have utilized mineral and organic natural colorants for millennia. The well-known technique for decorating interior facades in Damascus, based on the use of colored pat applied to carved lime stones to create floral and geometric shapes, dates back to at least the Mamluk period. Several European firms, including those belonging to the cement tile factories, exported organic and mineral dyes to Syria and Lebanon. 109 Indeed, this is the company Farbenfabriken Bayer, in Leverkensen, Germany, whose large exports to Syria were underscored by the French commercial delegation to Damascus in 1949. 111 Later, in 1953, another report from the French commercial delegation to Damascus mentions several German firms represented in Syria during the colonial and postcolonial periods that worked in the sector of organic and mineral dyes112: Farbenfabriken Bayer, Badische Anilin & Soda Fabrik, Schmiche Fabrik Kalk, C. A survey of the field, as well as the project statements for many initiatives, such as the construction of the British Consulate in Damascus in the mid-1930s, give significant examples. Nonetheless, undertaking a widespread field survey on the subject presents certain difficulties, not least because of the current war in Syria, but also because of the demolition of many buildings related to the studied period. Figure 2a: Hydraulic press imported from Germany by Sioufi workshop in Damascus. 33 Secondly, the sales invoices of the Lachave & Fils firm reveal that the frequently ordered dividers from Syrian and Lebanese manufacturers were numbers 1, 25, 31, 34, 36, 38, 61, 66, 73, 82, 87, 91, 103, 122, 125, 175, 176, 197, 198, 205, 206, 363, and 364 (fig. Additionally, several invoices indicate the sale of dividers with designs realized by the Syrian or Lebanese customers. Al-zanbaqah (carnation), al-‘amīr (the prince), al-musaddas (the hexagon), al-mušaqqaf (the divided), al-tāj (the crown) and others employed in the workshop of al-Kurdi in Damascus are relevant examples (fig. Figure 3: Models of cement tiles dividers, produced by Lachave & Fils firm, used in Syria and Lebanon. Figure 4: Local and imported models of cement tiles, used in buildings in Damascus. Nazir al-Kurdi (owner of a cement tiles workshop in Damascus area). 5: Dividers produced in Damascus, 1930s-40s, utilized in N. al-Kurdi cement tiles workshop, Damascus. 123 Later, in 1944, in his analysis of the disadvantages of “modern architecture” in Damascus, Kurd ‘Alī showed that stone, armed concrete, brick, and tiles had become the main construction materials in Syria. In any case, clarifying the sources and quantities of imported cement tiles requires investigation into the importations across all Syrian and Lebanese borders, which seems difficult in the framework of the present survey. 36 At first, French and British reports dealing with commerce in Syria and Lebanon during the late Ottoman period did not indicate the exportation of cement tiles. For instance, a British report126 published in 1913 on the Trade and Commerce of Beirut made note of the most important French exports, including several construction materials such as the iron, steel, copper, tools, plate glass, nails, varnishes, spirits, roofing tiles, and cement. Another report, published in 1913,127 revealed the main importations to Damascus, which included several materials for construction such as the copper, tin, and zinc plates. For instance, during the first quarter of 1932, Syria’s and Lebanon’s imports of cement tiles attained 6,695 tons, valued at 32,600 Syrian pounds,131 compared with 116,616 tons of pottery, valued at 692,750 Syrian pounds (in other words worth nearly twenty times more). 132 In the same quarter, the value of cement tiles produced in Lebanon alone attained 35 million Syrian pounds. 37 Additionally, the French catalogues of foreign trade and général du Commerce et de la the exportation of cement tiles around the world and point to modest quantities exported to Syria and Lebanon. Before 1918, Syria and Lebanon were part of the Ottoman Empire, and their importations from France were grouped with those of the Ottoman Empire. 134 Did some arrive through Syrian and Lebanese ports? We do not have a clear response. The French catalogues of foreign trade and navigation nonetheless offer significant but not exhaustive data on cement tile importations to Syria and Lebanon, designated until 1946 as one political entity: “Syria. 70/Syria and Lebanon. 40/Syria and Lebanon. At the same time, the development of local manufacturing was accelerating due to several factors: the easy process of manufacturing; the local production of most of the parts required for the workshops’ tools by the mid-1930s; the customs union between Syria and Lebanon as well as the promulgation of several customs treaties with neighboring countries; the establishment of a developed railway network connecting most Syrian and Lebanese cities to others and to Palestine, Jordan, Arabia, and Turkey; the official reforms undertaken during the late Ottoman period and the French Mandate targeting the development of local industries, particularly concerning legislation, transport, and customs regimes; the abundance of raw materials, at first imported then local produced. Nonetheless, this situation experienced the repercussions of the 1929 international economic crisis, which contributed to a severe reduction in European exports to Syria and Lebanon, including construction materials. For instance, the value of French exports to Syria and Lebanon fell from 194,426,980 French francs in 1930 to 139,355,420 French francs in 1931. 136 The result was a general stagnation in the Syrian and Lebanese economies beginning in 1930-1931,137 simultaneous to a virtual cessation of importation and a clear increase in local cement tile production. 39 The present survey demonstrates fundamental aspects related to the historiography of the importation and local manufacturing of cement tiles in Syria and Lebanon from the 1880s to the 1940s. It elucidates the emergence, evolution, decline, and revival of many construction materials and techniques throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. In other words, it underscores that the importation and local manufacturing of cement tiles could not be isolated from the modernist architectural debate and the promising economic context that characterized Syria and Lebanon from the Egyptian Expedition (1832-1840) onwards. Nevertheless, several points, concerning imported cement tiles from Italy, the importation of related machinery from Germany, and Syrian and Lebanese customs statistics should be further clarified. 40 The documentation brought to bear here shows that Europe—and France in particular—was the main exporter of the cement tile technique to Syria and Lebanon. It also suggests that the first manufacturing workshops were established in Beirut in the late 1880s, then in Damascus at the end of the 1890s. European trade companies, based especially in Marseille, assumed the first sales of machinery for workshops in Syria and Lebanon. By the 1900s, local commercial companies specialized in the trade of machinery and construction materials played the main role in the importation of tools for cement tile workshops. In this framework, the Lachave & Fils company, the first French manufacturer of machinery and production tools, was most present in the Syrian and Lebanese markets. Statistics of the French, Syrian, and Lebanese customs demonstrate insignificant importations, of mosaic tiles only, during the Mandate. 42 While European ceramic tiles dominated the Syrian and Lebanese market because of mechanical manufacturing, cement tile production maintained its position due to its technique. Not until the 2000s did Syrian and Lebanese markets witness the return of a limited production of mosaic cement tiles, expressing the revival of an aspect of the heritage of nineteenth- and architecture. This observation, as well as the demonstration that most Syrian and Lebanese cement tile manufacturers have adopted European designs and others related to local architecture, prove that the modernization of Eastern Mediterranean architecture in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries occurred through the articulation of local and Western techniques and references. In any case, the use of cement tiles has affected interior and exterior design, creating new ways of engaging with space and an additional tool for expressing the historical context of both Damascus and Beirut. 1 According respectively to Muḥammad Kurd ‘Al ī , Ḫoṭaṭ aš-Šām, Damascus, Maktabat an-Nouri, 3rd ed, 1983, vol. 65-111; and Aḥmad al-‘Allāf , Dimašq, Damascus, Wizāraẗ al-Ṯaqāfaẗ wa-al-Iršād al-Qawmī, 1976, p. 5 ‘Ādel S ṭ ās , “Tahseen ṣifāt al-balāṭ al-‘ismanti bisti’māl mawād maḥaliyyah,” Damascus University Journal, vol. 10 On this subject, see Stephan Weber , Damascus, Ottoman Modernity and Urban Transformation 1808-1918, 2 vols. , Aarhus: Aarhus University Press, 2009 (Proceedings of the Danish Institute in Damascus, 5); and, Anas Soufan , Influences occidentales et traditions régionales sur l’évolution urbaine et architecturale des villes arabes, de la fin du xix e siècle au milieu du xx e siècle, l’exemple de Damas, dissertation, École Pratique des Hautes Études, Paris, 2011. Nazir al-Kurdi, Damascus, March 1, 2014. 277; about the commercial linkage between Damascus and Beirut, see also La Courneuve (France), Archives diplomatiques, 50CPCOM/91, Mf. 19 On the Syrian economic policies towards Lebanon during the 1940s and 1950s, see Khālid Al-Azem , Muẓakarāt, II, p. 24 Damascus imported cement and other European products through the port of Beirut from the end of the nineteenth century. 2, Affaires diverses 1924-28, report on the customs service in Syria, 1926, p. 27 Regarding the Syrian Modern Style, see “The appropriation of Syrian urban space by an Islamic art in the era of modernity: Case of Damascus 1839-1963,” lecture at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, November 9, 2015; Anas Soufan , op. in Marseille purchased molds in 1910 from the Lachave & Fils firm on behalf of a Syrian client. Araman was the principal actor in the manufacturing of concrete pipes and the establishment of Beirut’s drinking water and sewage networks during the French Mandate, establishing several factories for concrete applications, in addition to producing and trading equipment, petrol, and many construction materials. Nazir Al-Kurdi, Damascus, March 1, 2014; with Mr. Muhammad Awwād, August 2014. Nazir Al-Kurdi, Damascus, March 2014. Nazir Al-Kurdi, Damascus, March 1, 2014. 77 See Damascus (Syria), Archives of the Marble and Cement Products Artisans Syndicate. 3, Affaires diverses 1922-23, report on the “Economic Situation and Value of Syria and Lebanon,” no. Nazir Al-Kurdi, Damascus, March 1, 2014; and with Mr. Muhammad Awwād, Damascus, August 2014. 82 Palestinian manufacturers were the main Arab exporter of cement to Syria. In 1934, a commercial struggle was caused by rising costs of transportation of Palestinian cement to Syria by the D. See on the subject London (United Kingdom), Archives of the Foreign Office, 371/17947, E, Syria, sheet no. 83 The Société des chaux & ciments Romain Boyer was the main exporter to Syria. 2403, sheet 43, correspondence on the prices of construction materials determined by customs services, June 4, 1930. Muhammad Awwād, Damascus, August 2014. 95 The domination of Dalmatian cement since the end of the 1920s was indicated in the economic bulletins of the FHC and by Syrian and Lebanese merchants such as Néjib Araman. (France), Centre des Archives économiques et financières, Carton 60376, French Commercial Delegate in Syria, Report no. 100 London (United Kingdom), Archives of the Foreign Office, 371/21914, E - Syria, sheet 145, Annual report, Economy (A), for 1937, p. 101 London (United Kingdom), Archives of the Foreign Office, 371/21914, E - Syria, sheet 145, Annual report, Economy (A), for 1937, p. 10, Economy Department, Syrian government, 1939, p. Nazir Al-Kurdi, Damascus, March 1, 2014; and with Mr. Muhammad Awwād, Damascus, August 2014. Nazir Al-Kurdi, Damascus, March 1, 2014. 110 According to a report issued from the French Commercial Delegation in Damascus: (France), Centre des Archives économiques et financières, Carton 60376, Report 90D, November 28, 1949. 112 According to a report from the French Commercial Delegation in Damascus, (France), Centre des Archives économiques et financières, Carton 60376, Report B/02/647, “Présidence du Conseil,” February 25, 1953. 116 In general, the economic bulletins during the Mandate displayed the prices of several construction materials. Nazir Al-Kurdi, Damascus, March 1, 2014. 7 (from the British Report for the year 1913 on the Trade and Commerce of Beirut and the Coast of Syria in 1913, V- no. 7 (from the British Report for the year 1913 on the Trade and Commerce of Beirut and the Coast of Syria in 1913, V- no. 2403, sheet 43, correspondence about the prices of construction materials determined by customs services, June 4, 1930; see also La Courneuve (France), Archives diplomatiques, 50CPCOM/336, MF. 40-41; see also on the economic stagnation in Syria and Lebanon at the beginning of the 1930s: Bulletin d’information, janvier 1932, p. Anas Soufan , « An overview of cement tile manufacturing and importation in Syria and Lebanon: , ABE Journal [En ligne], mis en ligne le 07 septembre 2021 , consulté le 23 novembre 2021 .

Read More ...

Until 2009, seven public companies were the only producers of cement in Syria. The Syrian cement industry is making remarkable progress in achieving the following objectives: .

http://www.re-buildsyria.com/building-materials-prices-in-syria-a-ton-of-iron-arrives-a-million-and-a-half-pounds-and-a-ton-of-cement-is-120000/https://oec.world/en/profile/bilateral-product/cement/reporter/syr

https://npasyria.com/en/63408/